The Council of Nicea Saves Christmas

Without the the Council of Nicea Christmas as we know it wouldn't exist

The Council of Nicea Was A "Christmas Game Changer"

The world was at peace. Constantine had defeated his rival and taken the helm of the Empire. He had ended the persecution of the Church. He professed faith in Christ. The Millennium could begin.

But it wasn’t that easy. Once the recurrent persecutions were over, it was safer and easier to profess faith in Christ—no matter how you lived, no matter what you believed. The Church had before it an enormous task of discipling the faithful and disciplining the unrepentant. In many ways the Church failed, but at one crucial point she succeeded—barely.

The story begins in Alexandria in Egypt. A presbyter, Arius, began to preach his own revision of who Jesus Christ really was. Arius was, at least at first blush, a rationalist. He wanted a God who made sense. The Christian gospel had denounced the polytheism of the pagan world. Well and good. But then the Church insisted that the Father is God and that Christ, the Son, is also God. But that’s two gods; that’s polytheism, Arius argued. Arius campaigned for unflinching monotheism; he campaigned for rational religion. Or did he?

An Old Fashion "Arian" Christmas

Arius insisted that there is only one God, the Father. The Father alone is eternal and uncreated. In his essence he is wholly unlike the created world. Like the God of neo-orthodoxy, he is ineffable in his transcendence, completely beyond our categories of description: “God himself then in his own nature is ineffable by all men. Equal or like himself he alone has none, or one in glory.”

So who or what is the Son? Arius said that the Son is the greatest of God’s creatures. He isn’t God, but only the Son of God, and that by adoption: “The Unbegun made the Son a beginning of things originated; and advanced him as a Son to himself by adoption. He has nothing proper to God in proper subsistence. For he is not equal, no, nor one essence with him.”

The Son, then, is temporal and finite. He can’t understand the infinite; he can’t comprehend the Father, and he can’t reveal him: “To speak in brief, God is ineffable to the Son. For he is to himself what he is, that is, unspeakable. So that nothing which is called comprehensible does the Son know to speak about; for it is impossible for him to investigate the Father, who is by himself.” God is forever silent, and not even his Son can reveal him, not in His incarnation and not through Scripture.

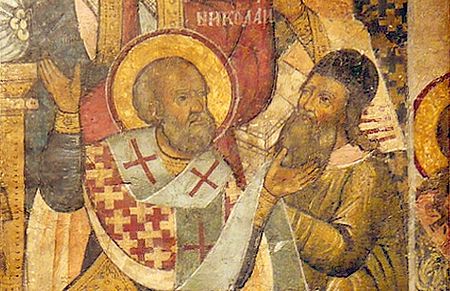

St. Nicholas slapping Arius upside the head at the Council of Nicea.

Arius And Arianism Kills Christmas

The Son, then, is temporal and finite. He can’t understand the infinite; he can’t comprehend the Father, and he can’t reveal him: “To speak in brief, God is ineffable to the Son. For he is to himself what he is, that is, unspeakable. So that nothing which is called comprehensible does the Son know to speak about; for it is impossible for him to investigate the Father, who is by himself.” God is forever silent, and not even his Son can reveal him, not in His incarnation and not through Scripture.

Arius went further. Since the Son is a created being, it would be possible for God to create other godlings as great as he: “One equal to the Son, the Superior is able to beget; but one more excellent, or superior, or greater, he is not able.” God could have many adopted sons, each a less than perfect revelation of the Father and yet each potentially more relevant culturally or historically than the others.

Arius wanted a rational religion, yet he placed his God beyond any sort of intelligible description. By this lens, we could never have Christmas as we know it.

Arius wanted a monotheistic religion, but he opened the door for a plethora of new gods. He wanted clarity in religion, but he dismissed Scripture as infallible, verbal revelation and left his followers with philosophical crumbs. He wanted Christianity but abandoned the self-revealing God and the divine Savior. He was left with nothing.

Arianism And The Council of Nicea

Constantine wanted to insure the unity of his empire. He knew, as most post-moderns don’t, that the roots of social and cultural unity are ultimately religious. A people, an empire, walks in the name of its God (Micah 4:5). Constantine knew his empire needed religious and well as political unity. With displeasure he witnessed the burgeoning Arian controversy. He tried low-key intervention, diplomacy and such: it didn’t work. So he tried something wholly new: he called together the first ecumenical council of bishops and presbyters in the Church’s history. Constantine wanted a unified, peaceful Church.

The Council met at Nicea in Bithynia. 318 bishops attended. The emperor paid the expenses of all the delegates. He made the logistical arrangements. He was present at the Council meetings. At a key moment he encouraged the adoption of biblical orthodoxy. And yet he never interfered in the Council’s deliberations or tried to force his own opinions on the Council.

Arius came to Nicea, and along with him a small number of his cohorts. They insisted that the Son is of a different essence (heteroousion) than the Father. The slightly larger orthodox party, led by Alexander of Alexandria and Hosius of Spain, insisted that the Son is of one essence (homoousion) with the Father.

The Council Of Nicea Uses Scripture To Refute Arius

There was also a large middle-of-the-road party led by the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea. For one reason or another, these bishops were unwilling to commit to the word homoousion. They preferred a word that differed by one letter, the word homoiousion. It meant “of like essence.” The Son was of like essence with the Father. He was like God. Just like God.

As is often God’s way, He stirred the pot to make compromise untenable. First, Arius spoke to the assembled bishops and made his position very clear: the Son is not deity; he is a mere creature. Much to his surprise, the bishops reacted violently. They would have none of Arius’s heresy. Arius had seriously underestimated the novelty of his position and the power of his writings. The Council quickly wrote off Arius’s position as heresy, but now it had a more difficult task. With what words could the council draw the line that would leave orthodox believers on one side while firmly placing Arius and his followers on the other?

For some time the Council talked through various Scriptural phrases. Surely one of them would serve as a litmus test for orthodoxy. The orthodox bishops “confronted the Arians with the traditional Scriptural phrases which appeared to leave no doubt as to the eternal Godhead of the Son. But to their surprise they were met with perfect acquiescence. Only as each test was propounded, it was observed that the suspected party whispered and gesticulated to one another, evidently hinting that each could be safely accepted, since it admitted of evasion.”

Clarity Of Nicene Doctrine and Christmas

In other words, Arius and his friends had been at this game for a long time. They had an explanation of some sort for every passage of Scripture that forth the Son’s eternal deity. The Council still looked askance at the word homoousion. It isn’t in Scripture. It didn’t have a long history of well-defined use. Maybe . . . .

About this time, Arius’s chief supporter, Eusebius of Nicomedia asked to address the Council. He believed that his faction was about to lose everything. Here again was the hand of God. Eusebius was probably wrong. But he felt compelled to testify against the orthodox position in the clearest, harshest language he could. And so he did.

The Council was aghast. Now the matter was crystal clear. Well, almost. Eusebius of Caesarea suggested a confession used by his own church as the solution to the problem. It was a good statement, and not unlike the one the Council finally adopted, but it lacked the word homoousion. In the end... the Council of Nicea gave us the first form of what we now call the Nicene Creed. It read in part:

"We believe in one God, the Father All Governing, creator of all things visible and invisible; And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father as only begotten, that is, from the essence of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not created, of the same essence as the Father, through whom all things came into being, both in heaven and in earth; who for us men and for our salvation came down and was incarnate, becoming human. He suffered and the third day he rose, and ascended into the heavens. And he will come to judge both the living and the dead. And in the Holy Spirit."

The Challenge Of Keeping Christmas Orthodox

Again, it would be nice to believe that Nicea settled the issue of Jesus’ deity once and for all. It didn’t. The controversies continued. But the Church had confessed Christ in the clearest possible terms, and later generations would continue to build on that confession: Jesus is God. He is the eternal Word of the Father. He is Yahweh come in the flesh. He is the Savior of the Word.

Copyrights are reserved @ Heirloom Audio Productions LLC.